5

The Research Finds A Home

So it was decided, with Moore's somewhat reluctant blessing, that the mountaintop laboratory in New Mexico Tech's future would be on top of South Baldy. Only two problems remained in the early-planning phase: obtaining permission from the Forest Service to blast and bulldoze a road through a national forest in order to erect a four-story building, and getting the money for the road.

Workman approached the problems with typical cunning and ingenuity. The mountain was in a national forest, was it not? So who should build the road? Why, the Forest Service, of course!

When Workman broached the idea in 1958, Regional Forester Fred Kennedy, like his superiors on the Potomac, did not favor the idea. He said that the administrative needs of the Forest Service would not be particularly well served by such a road. Kennedy did state, however, that since South Baldy was occasionally used as a forest-fire lookout, it would be nice to have a road. Finally, he promised that a ranger would be in touch later.

Workman had enough experience with bureaucracy to know when he was being given the brush-off, and enough patience to wait. In July 1959 he gave up on Fred Kennedy and wrote again to the chief of the Forest Service. Workman and the chief were acquainted, a fact Workman stressed in the letter. The reply, though, came from the assistant chief, who stated that most such roads were built for access to timber and that lack of funds limited the number of roads that could be built.

The reply was plausible, but Workman realized the real problem was one of jurisdiction. The Forest Service is officially responsible for a number of things, but supporting physics research is not one of them, so it wanted nothing to do with the lab. (This attitude would haunt the place for years.)

Frustrated in his attempt to get results from Washington, Workman went back to Fred Kennedy. This time, Kennedy promised to send a survey party to Baldy as soon as possible to estimate the cost of the proposed road.

In April 1960, Kennedy finally reported that several reconnaissance studies had been made in the area and that a review of the route, along with a preliminary cost estimate, were being prepared. By then, Workman was getting thoroughly tired of the delays, so he set about pulling every official string within reach. Soon the Chief of Naval Research and the head of the Arthur D. Little Company were writing to the Forest Service about the need for such a laboratory. The Forest Service replied that the ten miles or so of road could cost more than $100,000, and that Workman's need for the road was not pressing enough to squeeze out that kind of money.

As seen from Socorro rather than Washington, building a road up Baldy did not look like a $100,000 proposition. Workman's reply was couched in the courtly language he always used in dealing with high officials, but the point was perfectly clear. He said, in effect, "You guys are full of beans. I'm checking this out myself." And so he did. While Tech crews hiked up and down South Baldy, Workman wrote to New Mexico's senior U.S. senator, Dennis Chavez, telling him how much New Mexico's universities were contributing to defense research. He slipped in a mention of the problems with the Forest Service. It was not a plea for help--just a reference to the problem. Senator Chavez replied that funds should be available soon.

But not even a senator could light enough of a fire under the Forest Service to please Workman. By March 1961, he had a firm commitment to build a laboratory, but none to fund a road to it. Under this peculiarly intense duress, he gave up on the Forest Service and asked for $35,000 for the road in the final proposal to build the lab itself.

By making an estimate only one-third as large as the official one from Washington, Workman had thrown down a considerable challenge to himself. He sent physics professor Marvin Wilkening, mining professor George Griswold, and other faculty members up the east side of Baldy once again. This time they spent weeks hiking back and forth over the rugged terrain. The professors soon came to appreciate the irony of their mission. At the same time that they were enjoying the fresh air and beautiful scenery, they were trying to figure out how to blast and bulldoze a road suitable for diesel trucks all the way to the top of the mountain. After they examined the terrain and made a rough plan, Lamar Kempton of the R&DD would bring in surveying and construction teams to finish the job.

But Kempton's crews could not go right in with chainsaws and dynamite. Conservationists, hunters, and ranchers all voiced their opposition to the plan at a public hearing on August 6, 1961. This time, though, the senatorially-prodded Forest Service was on the side of the scientists. Clay Withrow, head of the Magdalena Ranger Station, came out in favor of the road, noting that it would open the area to hunters, hikers, and firefighters. (The local hunters actually did not care for that idea; they did not want to make access any easier for hunters from other areas.) Withrow even offered to attend the next protest meeting to explain the purpose of the road and its benefits to the public. The persuasiveness of Wilkening and Withrow was such that the next protest meeting never took place.

Some of the objections were based on the proposed location of the road. The most beautiful scenery in that part of the Magdalenas is on the east face, an area of sheer cliffs and tall pines along the sides of Water Canyon. Building the road up the east side would leave a ten-mile scar zigzagging up the side of the mountain. Circling around the north end of the mountains past the village of Magdalena and going up the west side of South Baldy would have been technically easier and esthetically less damaging. It would also have made access easier for the Forest Service, which had its ranger station in Magdalena. But it would have added about twenty miles to the researcher's daily trip up the mountain. Practicality won out, and the survey crews went to work.

It was then that Workman unveiled his secret for doing the $100,000 job for $35,000. There was no need to hire expensive outside contractors; Kempton could do the entire job with a crew of experts from TERA, the Terminal Effects Research and Analysis group that was part of the R&DD. Kempton and Kenny Sorensen, his right-hand man from TERA, walked and rode horseback up and down the route suggested by Wilkening and his group. Trying to match the road with the terrain, they decorated the mountainside with dozens of rolls of surveyor's tape, using every available color and finally resorting to combinations of colors.

Finally, one summer day in 1961, Kempton took a forest ranger on a hike up the only acceptable route. The Forest Service agreed to the plan on the condition that Kempton himself would be in charge of everything. The final approval for construction would have to be obtained half a mile at a time, and would depend on the quality of the work done on the previous half mile. Under those terms, the Forest Service raised its official estimate to $220,000, with a projected completion date of December 31, 1967.

| |

|

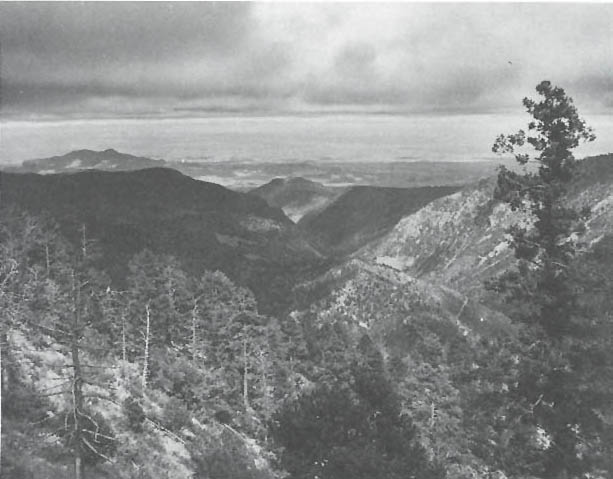

Looking down south Water Canyon to the Rio Grande Valley. Marvin Wilkening photograph. |

The Forest Service should have known Workman better by then. Given enough money, enough manpower, and a free hand to administer both as he saw fit, Workman could probably have finished the interstate highway system by December 31, 1967, and then pitched in on the space program. By February 1962, the road had been roughed out all the way to the top.

Rough was exactly the word for it. Most of the road was cut with bulldozers (one on loan from TERA and two brought in from outside, along with their operators). Everyone had standing orders to make the most of all available daylight; this meant that the pair of hired "cat skinners" lived five days a week in a trailer at the site, while the TERA workers had the dubious privilege of commuting to the site by daybreak. About 5 percent of the road had to be blasted out of solid rock. Kempton did the "powder monkey" work himself.

Along with the road was built the first of the Langmuir traditions: the assignment of nicknames and folklore to inanimate objects. The first switchback was dubbed Lone Pine Turn. Kempton informed the crew that the lone pine at the curve was holding up the sky and that anyone who took an axe to it would be extremely sorry. Above it came Barber Pole Turn, with a tree wrapped in two colors of surveyor's tape, and then Kemtown, named after the boss, where there was room for the Cat skinners to park their trailer. Near the top, the road made an S-curve through a stand of tall pines. The fellow who had to cut the trees observed, "Sure woody up in here." The curve became known as "Sure-Woody" (to the old-timers who remember the origin of the pun) and as "Sherwood Forest."

While the roadwork continued, Workman applied for Forest Service permission to build the laboratory. Along with the request for a permit, he sent a seven-page supporting statement, with pictures, detailing how the lab would be built and what it would look like. He had designed the structure himself, acting as both architect and engineer. The plan called for four enclosed floors and three decks. The foundation was to rest on bedrock. Workman wanted a building that could shrug off 150-mph winds, three-foot ice accumulations, and as many direct hits by lightning as the mountain could attract.

|

|

|

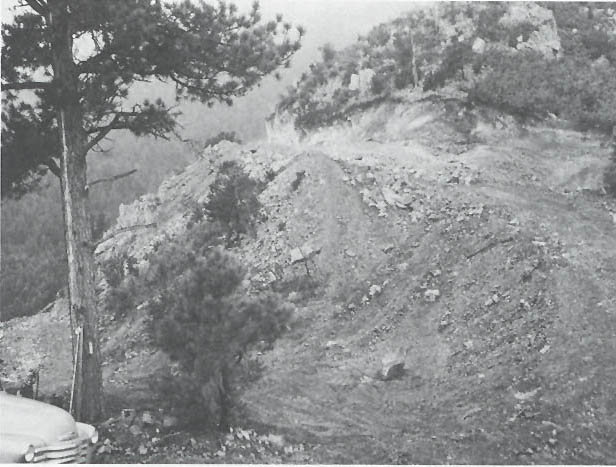

A bulldozed portion of the lab road.

|

In March, Workman wrote to Langmuir's widow:

I need to have your permission for doing something that I have wanted to do for a long time. We are building a building under the auspices of the NSE The building will be located on South Baldy Peak in the Magdalena Mountains. That is a nice sharp peak to the west that was visible from your apartment. The building is going to be a nicely conceived affair, artistically developed and dedicated to the study of atmospheric physics, which subject was brought from very early stages of childhood through adolescence by Irving. All of us want to call this building the Irving Langmuir Laboratory of Atmospheric Physics.

That same spring, Workman rode to the top of South Baldy Peak with Kempton and Sorensen. The day was cold and windy, as springtime in the mountains of New Mexico is apt to be. They sat on the peak to eat their lunch and admire the view. To his surprise and disappointment, Workman could not see Tech from the summit. The top of Socorro Peak, on the western edge of the Tech campus, was in the way. He began to grouse about how much trouble it would be to blow away the top 150 feet of Socorro Peak to permit line-of-sight microwave transmission between the lab and Tech.

Kempton had no desire to blow the top off Socorro Peak, cut a notch in it, or do anything else along those lines, so he suggested riding out along the ridge that ran southeast from Baldy. Workman was sure that the knoll on the end of the ridge would be too low, but Kempton insisted that they at least look at it. When they got there, trees sheltered them from the wind, the birds were singing, and they could see straight to Tech. Workman decided then and there to move the lab site.

Workman made some changes in the plans while the lab was under construction. The biggest change was the substitution of one floor and an enclosed turret for the original four floors. (This cut costs and also gave them exposed decks that would later be used to mount equipment.) The basics, however, remained the same. The primary design goal was to make the building a Faraday cage--a completely enclosed conductive structure that would protect the occupants from lightning.

|

|

|

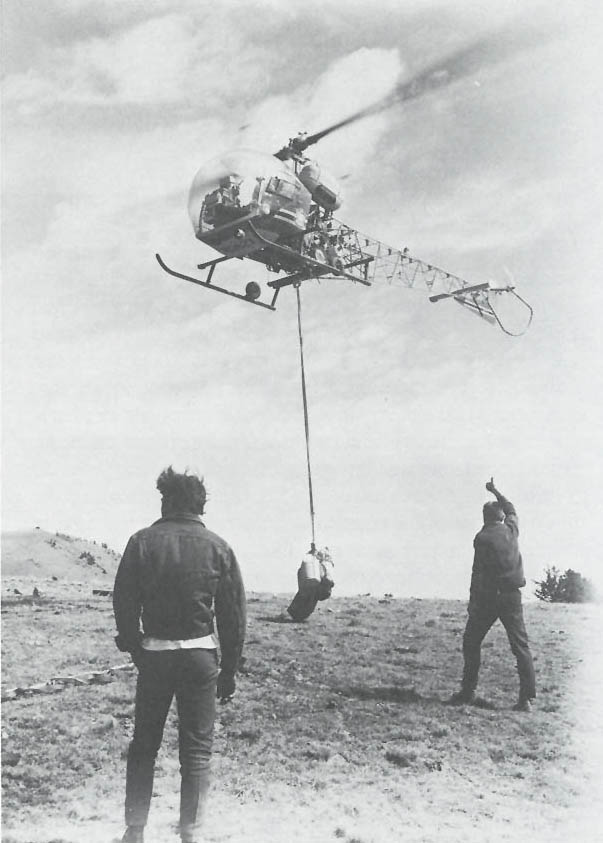

Charlie Moore gives the thumbs-up to a

chopper pilot during the construction of the cable across Sawmill Canyon.

|

Workman's pride and joy was the rotating cupola atop the lab. The parts of the cupola, including the giant ring gear at its base, had to be built at the TERA machine shop. The idea was to enable cameras and other instruments to be rotated to track moving storms and other phenomena. A matching cupola was built for the tower of the Research Building on the Tech campus. The Langmuir cupola was rotated only in 1964 and 1965, when Brook mounted cameras and microwave antennas in and on it while studying the electromagnetic spectrum of lightning. Shortly thereafter it was put out of commission by dirt in the large bottom bearings. Repairing the cupola would have been expensive and difficult, and the rotation feature was no longer needed for any specific project, so the cupola was left in position. However, the big knife switch tempts idle hands to this day.

Construction of the lab began in the summer of 1962. Kenny Sorensen was the chief construction engineer for the project. This time, a local contractor was hired for the actual construction, but Workman was still saving money. Most of the materials were military and other government surplus, obtained free or for the cost of shipping. Workman would browse through TERA's storage yard for Army surplus, searching for Good Stuff, and say, "I'm not stealing this, I'm merely liberating it."

Workman had not spent much time on the site during the construction of the road, since roads were not really in his field of interest. But once the construction of the lab began, he made his presence felt. The statement he had made when the Research Building at Tech was being put up--"I want to approve the hammers that drive every nail into the wall"--turned out to be a good description of how he ran the Langmuir project. Sorensen was in charge, but everything he ordered and did had to carry Workman's approval.

A few problems did arise. One of the workers rolled his four-wheel-drive Scout off the mountain; he survived, but the Scout was mortally wounded. Someone found a fawn with a broken leg and took care of it, sending Sorensen into town for a baby bottle with which to feed it.

When winter arrived, the crew quit work, as South Baldy is no place to be doing outdoor work in the winter. Since the bottom portion of the lab, the living quarters, had been completed, Workman looked for a live-in watchman. He found Floyd Reynolds, a survivor of the Bataan Death March. Reynolds also managed to survive winter on Baldy. His home in the lab was self-sufficient. Rainwater was collected on the roof and stored in a buried railroad tank car (surplus, of course). It was then pumped back up through a filter and gravity-fed into the lab. A diesel generator provided electricity. Reynolds brought his wife and a winter's provisions and kept an eye out for roving vandals.

But the hoodlums never got around to snow shoeing up the 10,000-foot peak. The lab was finished during the summer of 1963 and was dedicated on the Fourth of July.

Next: Chapter 6 -- The Sorcerer's Apprentice

Previous: Chapter 4 -- The Plains of San Agustin